Derrick Ofosu Boateng

Can you take us back to the defining moment that steered your interest towards photography?

There was a camera in my family, a simple point-and-shoot analog model, which we all used. I couldn’t stay away from it; I’d shoot a full roll and then have it developed. That was my first encounter with photography, but then my camera broke and I came to a standstill. This all changed when my father bought an iPhone 7, a groundbreaking device for us at that time. I was blown away by its capabilities and the instant visual feedback. I’d take every chance to snatch it away from him to take pictures. Although he felt displeased at first, when he saw the fruits of my creativity, he shifted from frustration to pride. He even ended up giving the phone to me, and the rest is history.

Following that initial spark, what was the breakthrough moment or scene that elevated your artistic journey and brought you into the spotlight?

Around the time I began sharing my photos on Instagram, the algorithm seemed to favor longer viewing times for static content. It looked like people who encountered my photos spent quite some time observing them. This increased watch time boosted my content’s visibility on feeds. As a consequence, my work reached a wider audience, from contemporary art enthusiasts to collectors, and I eventually caught the eye of Common’s creative team. They licensed two of my photographs for the first and second parts of his albums ‘A Beautiful Revolution’. This acclaimed collaboration spotlighted my work, garnering great attention and essentially launching my career.

What key elements converge to shape your distinct photographic style?

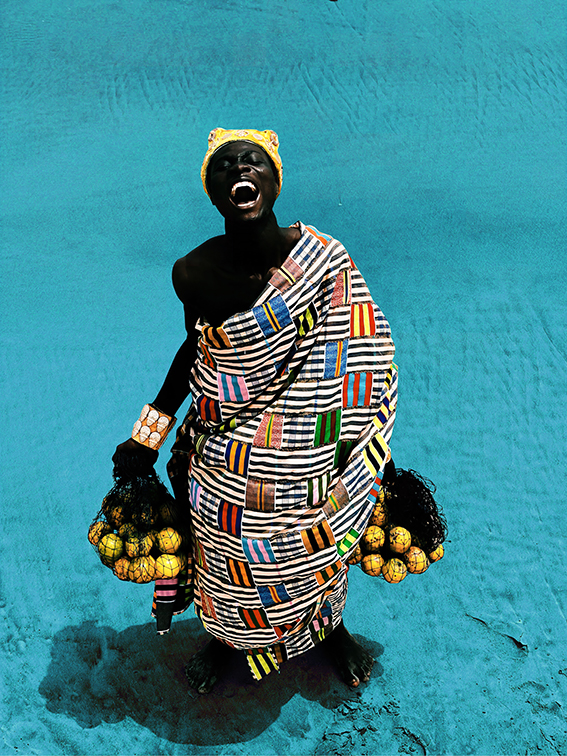

While color might be the first thing people notice about my work, it’s culture that truly forms the foundation. I’ve forged deep bonds with members from my community, and they’ve become the main characters in my creative canvases. Every detail in my work is thought out, with culture and color taking center stage.

What central narrative do you aim to convey about African culture through your photography?

From a mainstream, predominantly Western viewpoint, Africa is often painted in a negative light. My aim is to correct this misperception, using my art to accurately depict what African culture truly embodies and represents. To me, that includes our unyielding optimism, pride, unity, sense of family, resilience, beauty, success and rich traditions. And, of course, the embodiment of positive expressions such as joy and happiness.

Considering the emphasis in your work on Ghanaian proverbs, what compels you to intertwine these cultural aphorisms within your oeuvre?

My father is an elder in my community; a respected figure who helps preserve our culture and guides the younger generation. He greatly influenced me, as a passionate narrator of proverbs and a source of wisdom. Proverbs lie at the heart of African culture, offering timeless teachings and life lessons passed down from generations. Traditionally, these proverbs were orally transmitted and seldom written down, resulting in a lack of large-scale documentation. Each of my photographs is inspired by a proverb, serving as a means of documenting them and interpreting them, from a new perspective.

What led you to the inception of ‘Hueism’, and could you expand on its fundamental philosophy within the scope of African Art?

Historically, there’s a significant lack of African movements in the art space. Claiming an art movement is a powerful way to share your message, and in my case, to address the misinterpretation of Africa. It’s not just a declaration; it’s also a call to participate. The term ‘Hueism’ is derived from the word ‘hue’ which is synonymous with ‘strength of color’ and revolves around self expression through color therapy and visual poetry. These are my guiding principles, but they’re open for personal interpretation. In my work, I use proverbs for my ideation process, which sets me apart from other artists.

How does color therapy intertwine with your vision of Hueism? Could you clarify its role and interplay with this artistic paradigm?

In contrast to color theory, which focuses on the art and science of color usage, color therapy centers on how colors can influence our moods and perceptions. It explores how they can evoke emotions, and through my color depictions, I hope to foster healing. If someone is feeling depressed and looks at my work, I hope they feel lighter and uplifted. I’m working on deepening my understanding of colors and their effects, which is why I’m also speaking with certified international color therapists.

Your work employs a powerful chromatic language. Can you dissect a few of these colors, revealing the significance and semantic nuances they embody in your art?

Colors are deeply embedded in African culture; they’re undeniable and everywhere. From the Pan-African flag to commonplace objects, and of course, fashion. As a child, I could predict my mother’s movements based on her attire. Black and red meant she would be attending a funeral, while white indicated she was going to church. This conscious and purposeful use of color is something I’ve incorporated into my work. Take ‘A Gift from Mama’, for instance. Upon close inspection, you’ll spot the Ghanaian colors in reverse. The baby is swaddled in purple foil, a color symbolizing royalty. Each shade communicates a different idea or concept. But color interpretation is subjective of course, and I’m just as much interested in the perception of others.

As more and more Accra-based artists adopt elements of your craft, how do you envision Hueism will unfold?

With its concept now firmly defined, I foresee that the next phase is branding via association, which is already underway. It feels like this shift is already happening organically, as more companies are showing an interest in my imagery. A standout example is the limited edition trunk I customized for Louis Vuitton, that I look back on with so much pride. It’s incredible to see that such a renowned fashion house genuinely wants to connect with my vision and, as a result, different cultures coming together. Parallel to this, is the development of what I like to refer to as ‘iconography’; capturing notable figures and celebrities in my distinct visual style.

Transitioning from the ephemeral medium of Instagram to the tangibility of a book offers a new dimension for engagement with your work. How do you envision this shift will alter or enhance the audience’s interaction with your art?

I believe my book brings you closest to seeing the world through my lens. I feel that my art needs to be experienced in a tangible format to fully appreciate its impact, which is an entirely different mode of consumption compared to social media. It’s comparable to owning an exhibition of my work, but in this case, it fits right in the palm of your hand.

Can you shed light on the significance of the Ghanaian wood carvings that inspired your 3D book cover, and how you’ve reinterpreted them?

Wood carving is one of the earliest forms of African art, and it’s one of the original mediums through which Africans expressed their creativity. Ghana particularly stands out for its wood craftsmanship, and this art form greatly reflects our culture. This 3D cover merges my modern art with this ancient craft in a manner that’s both recognizable and yet fresh, with a touch of color.

With remarkable accomplishments in your repertoire, such as album covers for Common, collaborations Marni, Louis Vuitton and international exposures, what aspirations do you harbor for the future?

Of course, there’s the book launch, but I’ve got many more thrilling projects underway. I’m currently working on an exclusive commission involving Usain Bolt. Other high-profile individuals I’ll be photographing include Grace Jones, Naomi Campbell and Edward Enninful. My focus is gradually moving towards formal celebrity portraiture, but my original tools and signature remain the same.